[On the occasion of an exhibition dedicated to the miniature, initiated by Simon Clark for Grey’s Wharf, Penryn.]

In an interview from 2020, the ex-scientist and sci-fi writer Peter Watts comments on ‘negetropy’ (JAMEEL: 45:40). It is a fallacious idea, he says. There is nothing that reverses the gradual heat-death of the Universe. Perhaps entropy can be retarded, that’s the most we can say. If we find the world miraculous, what we’re seeing is the retarding of entropy.

In a further brief comment Watts says that the world’s slowing of entropy is achieved through elaborate diversification evident in increasingly interdependent and interlocking systems. He points to the tragedy that climate change is giving rise to the steady eradication of species at a rate of 130,000 per year.

Maybe you are an optimist, proponent of a politics dedicated to the affirming of diversity, encouraging it wherever you find it, and so on. Fake diversity is everywhere. It depletes the world’s resources. Is a so-called ‘real’ diversity then a conserver of resources? In a certain sense, yes. Art emerges from nothing. In another sense the answer is no. In the search for art we will squander every resource.

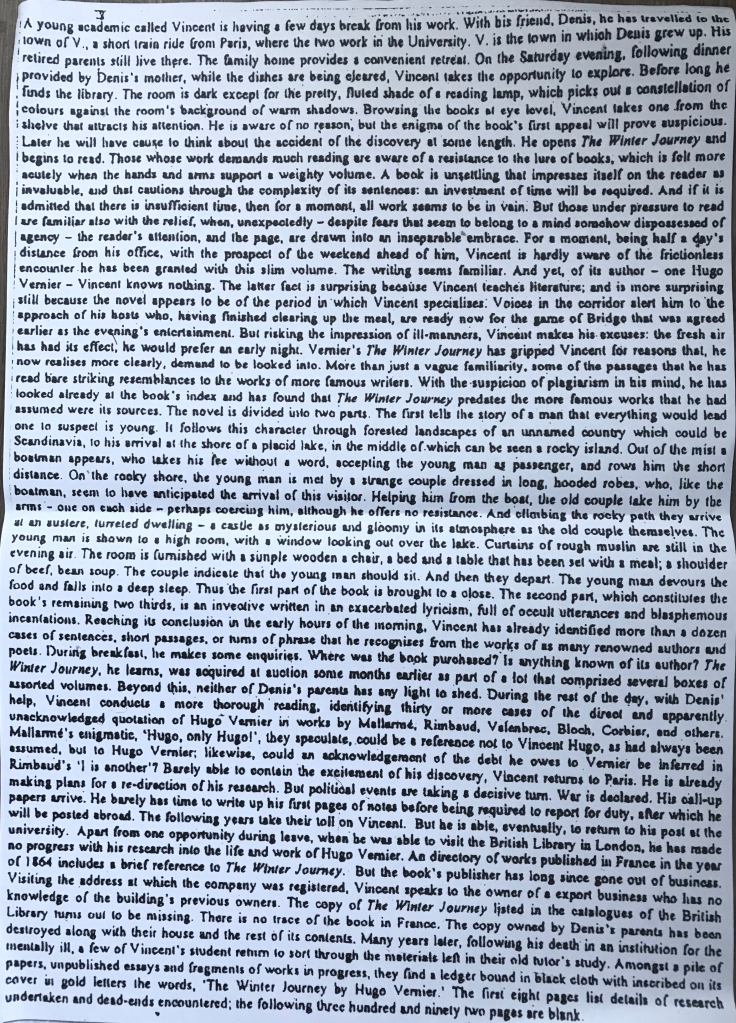

Reading this A2 photocopy page again a decade or more after it was written, one passage stands out: the sentences a quarter of the way down that describe what it feels like to be gripped by a piece of writing. Most often, reading is difficult. It’s a matter of stops and starts. Then sometimes, unexpectedly, the eye finds it can race across the page. Such moments are miraculous.

The photocopied page represents an impoverished version of a story by Georges Perec called The Winter Journey (1976)—impoverished because it is rewritten from memory. The story goes like this. A character named Vincent experiences a moment of compulsive reading. A book in his friend’s library attracts his attention for reasons he cannot quite identify. Then when he starts reading, he is hooked.

The passage in the rewritten version that stands out does so because it marks a limit of the rewriting exercise. It is the place—the most obvious place, maybe there are others—where the writing becomes more than a simple retelling of the story, where it begins to elaborate.

Perec’s biographer describes The Winter Journey as ‘one of the most controlled, most densely evocative prose texts that Perec ever wrote’ (BELLOS 1999: 677). To elaborate on Perec’s story is a travesty in at least two ways, first because it implies that piece might be improved while surely doing the opposite, and secondly because the rewriting procedure has broken its own rules.

*

Why rewrite The Winter Journey? Why even try? There are a few possible reasons. First, for those concerned to ask what it means to write and to do so as an artist Perec’s work is useful. His continual troubling of the discipline of literature has the effect of letting other practitioners in. The other reason it might be good to choose this particular piece is that it’s emblematic of the whole—at least so if the expert writer of his biography is correct. The exemplary quality of The Winter Journey becomes a licence. It frees the rewrite, allowing it to be read according to objectives not dictated by literature. And that in turn makes possible new propositions about what writing might be, not least as a practice in art.

Reason number two: The Winter Journey is already about rewriting, a different kind of rewriting, no doubt, but a rewriting all the same. It is a story about a book by a forgotten writer who appears to have been quoted widely without acknowledgement. What better way to understanding a story on rewriting than by rewriting the story?

The idea of a performative engagement, where reading a story involves writing it too, has appeared worthwhile also because of the suspicion that it would be difficult to achieve. From this point of view the unavoidable elaborations are valuable. They make apparent a quality of the writing process where ideas possess their own compulsion to emerge. Isn’t it what every writer longs for, the moment when writing, itself, begins to write?

And perhaps there is another level of engagement with Perec’s oeuvre here because of his dedicated use of writing constraints, which is to say sets of rules adopted almost as if they were a machine to produce the work. Paradoxically, the strictest constraint, the one that seems to eradicate the author’s creativity, also holds the most promise for something new. See for instance Perec’s Life A User’s Manual (1996).

But let’s say there’s one more rationale for the rewriting-from-memory of The Winter Journey. It is a reason that could not have been anticipated when the A2 photocopy was produced first and now allows the text in its material form to engage with a new context. According to Bellos, The Winter Journey is ‘the finest expression of Perec’s verbal art in miniature’ (667). A rewriting of the story has the effect of underscoring that miniaturisation. Even more, it miniaturises the miniature (at least it does so when it avoids deviating into elaborations!) Then again, those elaborations can be seen to mobilise another logic of miniaturisation, the same logic, perhaps, that drove Perec to perfect his writing style in The Winter Journey. When it succeeds, one of the miniature’s powers is to give rise to an explosion of potential. And that will appear marvellous because, for a moment, it delays the more fundamental cooling that all ideas, all matter, all life-forms are subject to in the long run.

BELLOS, David. 1993. Georges Perec: A Life in Words. London: Harvill Press.

JAMEEL, Daniel. 2020. Masters of the Universe Episode 1 – Peter Watts. [podcast]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1_YZZ9V3WU. [accessed 27 January 2022]

PEREC, Georges. 1996. Life A User’s Manual, Translated by David Bellos, London: Harvill.

PEREC, Georges. 1997. ‘The Winter Journey’, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. Translated by John Sturrock. London: Penguin.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

oversh Perec’s writing. So why rewrite The Winter Journey from memo

*

*

*